Sexey Beard felt appropriate to mention at the moment because of the ongoing fascination with ‘hipster beards’; a very annoying phenomenon for men like my boyfriend, who had a beard before it was ‘in’… However this particular person is actually a woman born in Somerset around 1780.

On 28 Mar 1809 in Worle, Somerset, Sexey marries a James Stabbins, and her name essentially becomes the title of one of those odd pulp fiction books from the 70’s…

I digress.

I have already covered the Sexey name’s connection with Somerset in a previous post – although something I found interesting when looking up this Sexey was that she was mis-named as ‘Sexa’ both on the 1851 census and again on her Burial record. This could be because the name Sexagesima was also in use at the time as a first name, presumably after Sexagesima Sunday, the second Sunday before Ash Wednesday in the Church, as well as Sex- names being used for the 6th child, although this was usually reserved for males and the name ‘Sextus’.

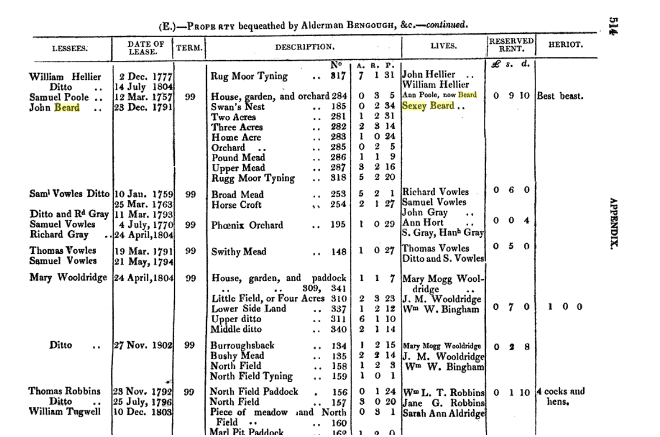

I could not find a definite entry for Sexey Beard’s baptism, however a simple google did find this entry from an 1831 report entitled Bristol charities: being the report of the commissioners for inquiring concerning the charities in England and Wales so far as relates to The Charitable insititutions in Bristol, edited by Thomas John Manchee (I guess he wasn’t too bothered about snappy titles)

So obviously workable farmland was provided to Sexey’s parents, possibly because of some kind of connection with Samuel Poole, a previous beneficiary. I am rather intrigued as to what the ‘Swan’s Nest’ actually refers to, if anyone can enlighten me please do! This also tells us that Sexey’s Mother was Ann Poole, and as there are no Beard’s marrying Sexey’s at all, we know Sexey does not refer to her mother’s maiden name. It could perhaps be from a Grandmother or other relative, or even a close friend as has happened in my own family tree, but because the word ‘sexy’ was not in use at that time to mean what it does now, it could just be that her parents heard the name and liked it!

The next we can definitely see of Sexey in written records is her marriage, but we do have quite a lot of info about her afterwards.

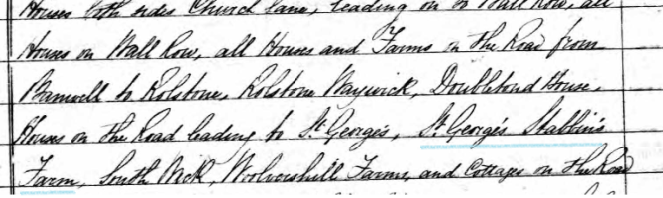

In the 1841 census, (where she has been transcribed as ‘Serge Stobbins’ – le sigh) we find her and husband James living in St George’s in Banwell (in itself an interesting parish) with their daughter Ann and James’ niece, also Ann Stabbins. I also found a baptism for a Patience Stabbins born in 1811. These seem to be the only two children they have.

James is a farmer, and although Sexey is widowed by 1851, she has now taken on the management of 46 acres herself. Her address is given as west Wick now but the two places border each other so it could well be the same land. Her daughter Ann is still living with her, as well as two house servants and one farm servant. Managing 46 acres could surely not be done by one man, so I’m guessing that she got an extra house servant so she could go out onto the farm, still working hard at 68.

1861 finds our Sexey living with her daughter, now Ann Crossman, married to Robert Crossman. I realised the children’s ages, 18 and 14, did not make sense, and the 1851 census for Robert confirmed that these were a previous wife’s children. That previous wife was in fact Ann’s sister Patience!

Patience had died in 1848, very sadly within a few weeks of her father’s James’ death, which must have been very difficult for Sexey. Usually in cases such as these the sister marries her brother in law quite quickly, somewhere away from home. Although it wasn’t uncommon for unmarried sisters, who had few options to support themselves besides marriage, to step in to care for the family for convenience, it was at the time illegal. This may be why they went away to Bristol to be married, as their local priest would certainly not have sanctioned the marriage.

The Bristol Mercury & Western Co. Advertiser, Eng. Sat. 16 June 1855. Pg. 16.

MARRIED June 10, at Christchurch, Bristol, Robert, eldest son of Mr. Crossman, of Wood-spring farm, to Ann, only surviving daughter, of the late Mr. James Stabbins, of Banwell.

This sort of marriage was made illegal by The Marriage Act 1835 – largely because of the belief in the Church that husband and wife “became one flesh,” therefore your wife’s sister was really your own sister. There was also some dubious science to back it up, claiming married couples become blood relations through some biological consequence of sexual intercourse. Some people also worried it would sanction husbands and their wives’ sisters lusting after each other whilst the wives were still alive, or that family trees would become too complicated and accidental incest would occur.

What ensued was six decades of petitioning to the government to overturn this rule and allow men to marry their wive’s sisters again.

It started in 1842 when a Marriage to a Deceased Wife’s Sister Bill was introduced and defeated by strong opposition, but it was fought again on the political scene almost annually.

Supporters of the act argued that prohibiting these marriages was unfair to the poor, (and perhaps in this case also the more rural folk who may have had less choice, Tom Cox has done an excellent piece on the challenges of rural dating) who could not afford to hire help and could not travel out of the country to get married.

The lengthy nature of the campaign even seeped in to popular culture – in the Gilbert and Sullivan opera Iolanthe (1882), the Queen of the Fairies sings “He shall prick that annual blister, marriage with deceased wife’s sister”, and Mrs Dinah Maria Craik wrote a book entitled Hannah, published in 1871, which tells the story of a man who falls in love with his deceased wife’s sister when he calls on her to care for his baby daughter (Mrs Craik had acted as chaperone to Edith Waugh when she travelled to Switzerland to marry the painter Holman Hunt after the death of his first wife, her sister Fanny).

Eventually, in 1907 The Deceased Wife’s Sister’s Marriage Act removed the prohibition (although it allowed individual clergy, if they chose, to refuse to conduct marriages which would previously have been prohibited). Interestingly it was not until 1921 that the Deceased Brother’s Widow’s Marriage Act was passed.

I realise I’ve been on a large tangent, however I’ve come across so many of these illegal sister-in-law marriages in people’s family trees I thought it worth mentioning. Not least because I’ve found that sometimes when people research their trees they concentrate on their direct lines, and often will not research a second or third wife, so will miss the connection entirely.

Back to Sexey in 1861 – now 81 and listed as a landed proprietor, so I imagine she was either receiving a small income from renting out farmland she still owned or may even have owned the farm they were all living on, as although it is not named on the sheet the front page of the census makes mention of a ‘Stabbins Farm’.

Unfortunately by the 1885 map the farm has been renamed, and in modern times the once very rural landscape is now sliced in half by the M5, with a few industrial estates built on it for good measure.

When she dies on the 10th June 1862, Ann is her sole executrix and Sexey leaves just under £200 (around £8,000 in today’s money), which is quite good for a Victorian lady who’d been a widow for some 15 years and is a testament to how hard she continued to work.

Fascinating as always. I often wondered why marrying your wife’s sister was frowned upon. I always learn great things from your posts.

Thank you so much! And thank you also for your mention of me on your blog. I lost the email (or postcrossing message?!) you sent me and then 6 months went by in the blink of an eye! So very sorry for my delay in replying. My health seems to be improving *crosses fingers* – one last MRI to check some tumours haven’t grown and now dealing with either ME (or Lymes, I think, waiting for bloods) but this is getting better too 🙂

There is always a great deal to study and think about when one does this kind of research.

Most interesting post!